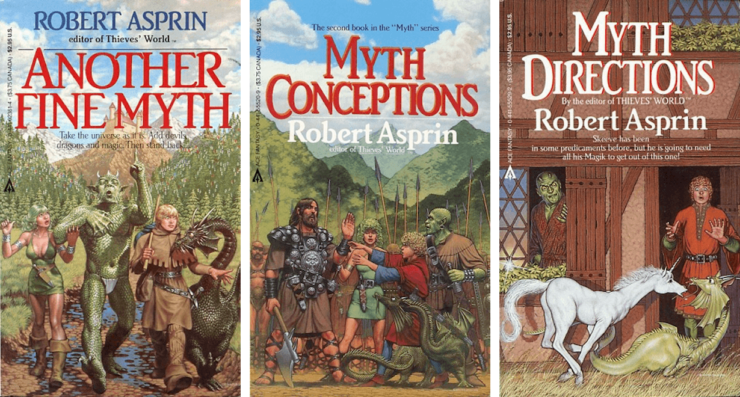

Imagine a series of novels—twenty or so, let’s say. They are sword-and-sorcery high fantasy involving alternate dimensions, monsters, magic, kings and queens, intrigue, danger, and lots of action. The two main characters have much the same chemistry as Sam and Dean Winchester, Aziraphale and Crowley, or Harry Potter and Ron Weasley, and the other characters are just as fun, funny, and engaging. The books have puntastic titles like Hit or Myth, Myth Directions, and M.Y.T.H. Inc. Link. Best of all, they’re funny. God, are they funny! Sounds like a literary property over which Netflix, Hulu—heck, all the streaming services should be fighting over, right?

Sadly, to my knowledge, there’s been nary a scuffle. Not a set-to. Not a tiff. The streamers aren’t even giving each other stink-eye over the rights to this series, Robert Asprin’s Myth Adventures, which began in 1978. (Before Good Omens. Before Discworld. Before Hitchhiker’s Guide.) In fact, the only person writing humorous fantasy back then was Piers Anthony, who grew up in Vermont but was born in England.

Come to think of it, the authors of the other books I just mentioned—Neil Gaiman, Terry Pratchett, Douglas Adams—are all English as well. Did Robert Asprin, who was born in Michigan and lived for many years in New Orleans, invent American comic fantasy?

Maybe not, but he did help to create, or at least popularize, something else: the shared world anthology. This type of anthology is a collection of stories by different authors using the same characters and setting. It is usually edited by the creator of that setting, who also writes and maintains the “bible”: a set of rules for how the world operates. Asprin’s anthology was Thieves’ World, which grew out of a 1978 dinner meeting between himself and two other writers, Lynn Abbey (whom Asprin would later marry) and Gordon Dickson. “As so often happens when several authors gather socially,” writes Asprin in “The Making of Thieves’ World,” a companion essay, “the conversation turned to the subject of writing in general and specifically to problems encountered and pet peeves.”

Asprin’s gripe was about the need to build a brand-new world for every fantasy novel. Wouldn’t it be cool, he mused, if there were already existing worlds that writers could use?

Dickson agreed. Abbey said that the ideal thing “was to be able to franchise one’s ideas and worlds out to other authors.” Buoyed by their enthusiasm Asprin started asking around, and he got a few writers, including Abbey but not Dickson, to agree to submit a story to an anthology that would be titled Thieves’ World. Then he and the group got to work creating the “bible,” which Asprin ran through a typewriter and mailed to all the contributors (how much easier this would have been with Google Docs!). Some dropped out of the project; Asprin replaced them. He also wrangled a publisher, oversaw the contracts, and found time to write his own story. The anthology appeared in 1979 and was acclaimed. A second volume appeared a year later, and a third the year after that. Thieves’ World now has 14 official collections, plus any number of unofficial ones. There are also seven novels set in the universe.

There are those among Asprin’s fans that maintain that, with Thieves’ World, he invented the first new literary form in 200 years, but he was too modest to accept those sorts of accolades. “What we did with Thieves’ World,” he said in a 1994 interview, “is no different from many TV series,” pointing out that shows like Star Trek have bibles for their writers, directors, and producers. Moreover, both Marvel and DC Comics had been using crossovers and other shared world elements for years. Aspirin introduced the concept to fantasy fiction, and the formula has endured. Without Thieves’ World, there might have been no Wild Cards. No Heroes in Hell. No Darkover anthologies.

Can someone at Amazon pick up the phone?

And there’s still more to choose from: In 1990, Asprin turned his comedic talents to science fiction with Phule’s Company, about the exploits of Space Legion captain Willard J. Phule. This was followed by Phule’s Paradise, A Phule and His Money, Phule Me Twice, No Phule Like an Old Phule, and Phule’s Errand. In all, Asprin wrote, co-wrote, or edited some 60 books over a 30-year career, many of them bestsellers. There would have been more if he hadn’t taken a break from writing in the late 1990s due to “a series of unpleasant events in my life,” not the least of which was a “five-year brawl” with the IRS. And, of course, if he hadn’t passed away in 2008 at the far-too-young age of 61. His works have been adapted into comic books, as well as board games and RPGs. But, astonishingly, nothing on the big or small screen.

My favorite Asprin effort will always be the Myth series. I was introduced to the books in 1987, my freshman year in high school, by my friend Andy, who lived with his father, brother, and sister. Andy’s parents were divorced. I, the son of a Southern Baptist pastor, knew no one else with divorced parents. Andy got mediocre grades, which I never understood because he was brilliant. He read Tolkien, Bertrand Russell, and Ayn Rand; he played D&D; he knew everything about Norse mythology. I learned about Douglas Adams and “Weird Al” Yankovic from him. Just before we lost touch after school, he sent me a postcard with Vincent Van Gogh’s famous self-portrait on the front. On the back, he encouraged me to “drop a line, lend an ear.” I still have some of the poetry he wrote (eat your heart out, e.e. cummings).

The first book in the series, Another Fine Myth, opens with Skeeve, a young magician’s apprentice, witnessing his mentor Garkin summoning an old friend—a green, scaly demon from the dimension of Perv. An assassin bursts into Garkin’s hut, and both Garkin and the assassin end up dead. The demon introduces himself to Skeeve thusly:

“Please ta meetcha, kid. I’m Aahz.”

“Oz?”

“No relation.”

Aahz is a wizard as well, but the summoning stripped him of his powers, and he can’t get himself back to Perv. Meanwhile, another magician named Isstvan has plans to conquer all dimensions, making himself their ultimate ruler. Aahz decides to stop Isstvan. With his teacher gone, Skeeve tags along. Many people they meet recognize Aahz as a Pervert—i.e., a native of Perv. (“It’s Pervect,” he corrects them toothily, one of the series’ many running jokes.) Skeeve, meanwhile, increases his magical skill thanks to Aahz’s tutelage. In the end, they defeat Isstvan, which sets them up for a bigger adventure in book two, an even bigger one in book three, and so on.

Roku, if you’re listening…

I hadn’t re-read any of the books for thirty years, though they’ve flitted across my memory now and then, especially the faux quotes that open each chapter. (My favorite, from Myth-Nomers & Im-Pervections: “Holy Batshit, Fatman! I mean…” –Robin.) Then I had a thought: has anyone done Asprin’s series as audiobooks? Turns out, someone has. Noah Michael Levine reads the series for Recorded Books, and he is outstanding. He gives Aahz a Billy Crystal-as-an-older-Buddy Young voice. His Tanda, a female assassin, is sexy but menacing. Big Julie, a military leader, sounds like a character straight out of The Sopranos. Gleep the dragon only ever utters one sound, “Gleep,” which Levine imbues with all sorts of meanings through his intonations. The Myth books lend themselves especially well to an aural medium because they are short, lively, and fun.

Buy the Book

Untethered Sky

…But they’re not completely frivolous. Skeeve starts out as a thief but grows in confidence and wisdom (though not in luck). His bond with Aahz is the series’ emotional core, and it progresses as well, from a mentor/mentee relationship to full partnership in an interdimensional detective agency. As for literary heft, one of Skeeve’s best spells is disillusionment: the ability to make others see what isn’t there. He relies on shifting identities over and over to confuse and confound, with mixed results—a device employed in many of Shakespeare’s comedies and which has been widely used ever since. There’s also an argument to be made that Asprin’s overarching goal was to affectionately satirize the familiar tropes and conventions of fantasy, and you can certainly read the series in that light.

Of course, not every novel has to engage our deeper literary sensibilities. Some can simply entertain. While the British humor of Gaiman and Pratchett and Adams certainly engages in its fair share of slapstick, whimsy, and puns, these elements are Asprin’s bread and butter. He excels at them—the more outrageous, the better. Just look at the ending of Myth Conceptions, in which Aahz and Skeeve, now court magicians of the kingdom of Possiltum, have vanquished an invading army and its commander, The Brute, only to be confronted by The Brute’s boss, Big Julie, who admits:

“I was getting a little worried about the Brute, you know what I mean? … He was getting a little too ambitious.”

“In that case. …” I smiled.

“Still…” Julie continued, “that’s a bad way to go. Hacked apart by your own men. I wouldn’t want that to happen to me.”

“You should have fed him to the dragons,” Aahz said bluntly.

“The Brute?” Julie frowned. “Fed to the dragons? Why?”

“Because then he could have been ‘et, too’!”

HBO? Peacock? Okay, screw it. I’m doing a YouTube series!

In the meantime, let’s hear from you—if you’re a fan of Asprin’s work, please feel free to recommend your favorite books, or your favorite puns! And are there any other fantasy or sci-fi works that carry on the spirit of the Myth Adventure books, and which have a similar sense of humor? Let us know in the comments…

Anthony Aycock is a librarian and freelance writer who has published in Slate, the Washington Post, Medium, the Missouri Review, the Gettysburg Review, and other venues. See more of his work at his website.

Thank you so much! I’ve been waiting for someone to highlight the Myth books. I first discovered them around 1985 when (I think) Myth-ing Persons was published. I also enjoyed the Thieves World Series. Tried the Phules books a few years ago and they didn’t strike my fancy as much. But Aahz and Skeeve remain two of my favorite characters in fantasy. I can’t not mention the amazing MythAdventures graphic novel with incredible art by Phil Foglio. I think it’s being reprinted soon – go to your local comic store and order a copy. You won’t be disappointed!!

I have heard that once there was an American fantasy magazine whose contents often included comedic fantasy. Sadly, this was a long time ago and its name is unknown.

That said, de Camp, Garrett, Myers Myers, Smith (not that Smith), and others wrote what were at least meant as funny fantasies, even if some of them have not aged all that well.

While Thieves World definitely established prose shared universes as notably commercially viable, it’s interesting (at least to me) to note decades of earlier efforts along those lines, some of which were commercial failures (the Twayne triplets) and others intended as one-offs (A World Named Cleopatra). Flipping through the pre-TW shared universes, the name Poul Anderson keeps appearing. He seems to have found the form intriguing. Unsurprisingly, he’s in TW.

Harlan Ellison’s Medea: Harlan’s World had its genesis in a 1975 seminar. Stories from it began to appear as early as 1978 and had things worked out differently, perhaps Medea would have been the book people remember as kicking off the Shared World boom of the 1980s. However, rather uncharacteristically for an Ellison project, Medea took a very long time to appear in book form, so by the time it did appear the boom was well on its way to collapsing.

I love the Myth books!! I still have them on my shelf. My favorite thing about them was how Skeeve led his crew. He had an unassuming way of inspiring loyalty and turning enemies into friends. The capers were fun but the crew dynamics were the best! Another character I liked was Bunny, who seemed like the stereotypical gangster moll but turned out to have a real talent for accounting!

I enjoyed the Phule’s Company books but only the first two that Robert Asprin wrote himself. The rest just aren’t as good.

Technically the HitchGuide radio serial also came out in 1978.

Oh my goober! I picked these up in the 80’s and still have the science fiction book of the month club edition. They are the only books I have ever reread.

I’d suggest that Asprin is actually one of two pioneers in the realm of 20th century American comic fantasy, the other being Christopher Stasheff, best known as the author of The Warlock In Spite of Himself and the cluster of interlocking series appearing in its wake. Stasheff’s overall tone is less slapstick than that of Asprin, and the fantasy often has a science-fictional element underlying it, but he shares Asprin’s devotion to the well-executed pun and the precisely aimed satirist’s arrow. Interestingly, while Stasheff’s first novel initially appeared in 1969, a full decade passed before its sequel appeared, at which point he published steadily for nearly two full decades.

A third key figure in the comic fantasy equation is Esther Friesner, who was writing funny urban fantasy (and quite a lot of other things) as early as the ’80s long before creating and shepherding the Chicks in Chainmail sword & sorcery anthologies. See particularly New York by Knight and Elf Defense for quality examples of her early work.

I was Tanda for Halloween in 6th grade. I’m guessing not everything in the Myth books has aged well, but I loved them as a kid.

I don’t know if this series fits your parameters, but I’ve always been a big fan of David and Leigh Eddings Belgarad series and the subsequent Mallorean. They follow relatable characters, some a bit stereotypical, on a quest to fulfill an obscure (at first) destiny. While the quest itself meanders across numerous realms, each following a different god with different attributes and mostly lackadaisical attitude toward being worshipped, the main characters are fun and fallible. You actually get to watch them grow to fit the roles chosen for them. I’ve seen no reason why they couldn’t be adapted to the big screen.

Asprin is one of the many writers I picked up from the Thieves World anthologies and I can truly say I’ve never found a bad book of his.

The Myth books had a short lived comic book adaptation by Phil Foglio of all people, super well done.

There are so many untapped authors of sci-fi and fantasy.

I’d love to see an adaptation of the Belgariad by David Eddings, or the Fuzzy books by H. Beam Piper, or the Matador books by Steve Perry, or the Deathworld books by Harry Harrison, heck, speaking of Harrison, why not Stainless Steel Rat?

In 1987, I was a freshman in college reading the first of the MYTH series.

I loved Asprin’s Myth series and Thieves World, back in the day. Was trying to get them in audio but they’re not available or expensive & my library doesn’t have them in any digital form. Now to see if they have physical copies…

But yeah, would love a visual media series with Skeeve & Aahz.

One of the best things about the Myth series is that the main characters are all good people that you’d like to hang around with. Violence is largely kept off screen (off page?) and most of the bad guys turn out to be not so bad. Usually they are also looking for a non-violent way out of any sticky situations.

lt has been a while since I’ve read them, but I believe they will age better than a lot of writing from the time. Any stereotypes Asprin included had holes poked in them quickly. Intelligent molls, bodyguards with a keen understanding of their jobs and its pitfalls, and a dragon with connections in an unexplained wyrm hierarchy.

It would take a deft hand to recreate many of the pivotal scenes including the Dragon Poker scene. Skiv just bets everything and lays down his cards explaining that as he can’t play the game at all, this is his best strategy.

One of the best forerunners of this kind of fantasy is The Incomplete Enchanter books

“First impressions, being the longest lasting, are of the utmost importance.” – J. Carter (Myth Conceptions Ch. 2)

A personal favorite because Burroughs was my first novel.

I started reading the Myth books back in elementary school, so I knew what a pervect was before I had ever heard of a pervert.

The early books were always my favorites and Skeeve and Bunny were one of my first ships.

I love how Bob was able to make every characters voice, internal and external, so different. It’s something I aspire to in my own writing.

Raise a glass, for absent friends.

Also, I recommend Spider Robinson’s Callahan series for those looking for a similar feel.

For heavens sake, stop arguing about which twentieth century writer invented comedic fantasy. Mark Twain invented it with A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. In 1899.

#16: Who’s arguing? Nobody here has tried to claim exclusivity for anybody except Twain…and by your own framing, Connecticut Yankee falls outside the scope of a discussion of 20th century material by virtue of being published in the 19th.

(If the foregoing sounds a trifle pedantic, it should; I suspect that both auspex and I are trying to skate too close to the line between “funny” and “sharp”, a line that Twain in particular is prone to dancing across.)

To better address the underlying issue: Connecticut Yankee is both a chronological and tonal outlier for purposes of the current discussion – what the present essay glosses over is that Asprin in fact was a major catalyst for a sizeable wave of pun-and-slapstick fantasy dating to the 1980s and early ’90s…and there actually is a noticeable tonal difference between the American and English writers from that period. (See Tom Holt for a further example of the British flavour.)

I happened to discover the first few Myth Adventures books in a relative’s house early in high school, and remember them very fondly. I really enjoyed the feel of a heist/scheme novel with fantasy trappings, and it was great fun to watch a cast of such vivid characters play off each other. The characters and the wordplay and the sense of fun and delight were very memorable.

Regarding the question of origins, if you really want to get into the “who invented comic fantasy” question, I feel like Lucian’s A True History has a pretty strong claim.

That said, there’s a difference between “the first ever to do something” and “the one who kickstarted a trend” and “the one whose work was the inspiration for a particular sub-genre”.

Another fantasy book with a similar devotion to punnery is The Case of the Toxic Spell Dump by Harry Turtledove.

Wow, I haven’t thought about these books in years. My dad and I read the Myth books and Thieves World and loved them.

To this day I use “We’ll burn that bridge when we get to it” whenever possible.

I’m a big fan of Thieves’ World. I’ve been meaning to re-read it for a while now. In fact, I signed-up for Audible with plans to listen to audio books only to find – like you pointed out- that they are not available in that format. What?!? I was so sure there were audio books of Thieves” World that I didn’t even check first.

I haven’t read much humorous fantasy but you’ve piqued my interest.

My gamertag, (since I was 20 or so,) says it all. Aahzmandias42. I was introduced to the series by my step dad when I was 12 or so. I’m 42 now and still occasionally reread the Myth books.

I never read a Myth Adventures book apart from Phil Foglio’s comics version despite seeing them often while haunting the F/SF department as a teen. Not sure why; I suppose it was just that there was always something else I wanted to try and/or continue with first based on habit or recommendations, particularly being at least near-completist about certain other authors. I remember enjoying a friend’s Thieves’ World anthology, but that led to more anthologies rather than more Robert Aspirin.

Oh, I agree with Jordan Lund @10 that The Stainless Steel Rat could make for a great series.

#20: “To this day I use “We’ll burn that bridge when we get to it” whenever possible.”

I also like to use that phrase but I completely forgot that this is where I got it from! Thanks for the reminder!

If we’re throwing in The Stainless Steel Rat, can we also add the Retief books by Keith Laumer?

The Myth series was great, at least mostly. Some of them I’ve re-read multiple times, and the first and third are a couple of the funniest books I ever read. And I do think that the whole Thieves’ World concept was groundbreaking. The books themselves were kind of patchy, inevitable with all the different writers, but they had some definitely good stuff.

I do feel like later in his life, after the IRS thing, It seemed as if Asprin had had a good deal of his sense of humour surgically amputated. The “Phule” books, despite one or two brilliant lines, were overall just not funny. They never had much sense of tension either; the whole “misfits come together and turn out to be brilliant in their different ways” thing was sort of heartwarming, but just too dashed easy to have much impact, especially with the main character’s mega-money backing them. I do remember one awesome joke line, though. The main character, who designates himself “Captain Jester”, is having a first contact meeting with aliens who use pretty good translation software, and it’s told somewhat from the aliens’ point of view. So the alien says, “Well, Captain Clown–“. “I’m sorry, but that’s Captain Clown.” “I . . . see.” Overall, though, it’s pretty thin stuff.

But when Asprin was good, he was very very good. Even some of his non-comedy stuff was impressive. The Bug Wars, for instance, has no human characters and conveys the culture and attitudes of the reptile protagonists in a way that not only shows them as fairly nonhuman but also shows cultural shifts over the course of the book that leaves you a bit in doubt as to how much of what you’re seeing is innate alien-ness, how much is culture, and how much is the individual personalities of the main characters, not to mention mindsets associated with caste identities. It’s a grim, tough book full of combat with giant insects and grimly pragmatic reptiles, and it keeps you reading. Even what I believe was his first book, theoretically co-authored with George Takei, is quite fun, with a ninja fencer trying to stop a large robot company’s self-aware machines who have gone genocidal due to a minor software error.

I loved the Myth Adventures books. Someone needs to bring them back into print. Or into ebook.

Phule’s company is also the BEST guide for managers and should be required reading. The principles he lays out for managing a team are stellar and work… every time. I have used it at mulitple locations and many times in my career.

I have all of the Phule books and I think I read through all the early MYTH books. Not sure what distracted me from them, but I see a visit to my favorite science fiction used bookstore is in my future.

OK, comic fantasy goes back at least to Apuleius, and farther if you consider the oral tradition and trickster gods. DeCamp and Garrett are two of the authors who were practicing when Asprin started. Heinlein wrote some fantasy short stories with humorous elements.

I’ve read some of the Phule books. They were a bit clumsy but entertaining. I’m going to give the myth series a chance.

I enjoyed the MYTH INC and Phule’s Company books…until others started co-writing them. So I stick to the earlier ones and largely disregard the later ones in each series. But I love the laughs.

They were good until he got writers block and had some one else do them. Went downhill from the first book afterwards. Sweet myth terry of life was really his last official book in the series. 1993. Next book was 2001

One of my favorite series of all time. Read and reread many times! Thank you so much for writing about it!

I read these when I was a kid. Even collected the trade paperbacks which the covers were drawn by Phil Foglio. They were great.

Another contemporary author I’d put in there for early fantasy comedy would be Alan Dean Foster. His Spellsinger series was a favorite of mine as well.

There was at least one issue of a graphic version of the ?2nd? book; I would swear that the artist was someone I hadn’t heard of before or since (the penname “Vanamonde” comes to mind, but that’s probably just a Clarke overlay), but ISFDB shows only two series, both done by Foglio. The sequeI made Skeeve look shifty/sly rather than relatively innocent, which spoiled the effect; the first series, with AFAICT Foglio doing some scripting as well as the art, was funnier than the book.

Asprin was multi-?talented?; he also created the Dorsai Irregulars (costumed guards for SF conventions) and their Star Trek spinoff the Klingon Diplomatic Corps; before them, he co-created the SCA contrast group the Dark Horde, which got him satirized in “The Cowherd and the Khakhan” (which isn’t findable on the net and ought to be).

Yesss- read “Myth…” while in the service, “Phule…” as well. Thanks, Tor, now I gotta pile of books to locate and reread. Sigh. Read the comments through, Harrison’s Slippery Jim deGriz a cinema thing? Oh H*LL yes. Can I suggest he be portrayed by Nick Cage? Or maybe Keanu Reeves? And Laumer’s hilarious “Reteif of the CDT” series would work well as a streamer or cinema series- this role requires someone younger than Reeves or Cage, who also is fluent in action/comedy. May I suggest Taron Egerton, young Eggsy from the “Kingsman” films? What surprised me is that no one mentioned Fritz Lieber’s outstanding “Grey Mouser and Fafhrd” books. Ripping good sword and sorcery, and often hilarious for adults (read these in Jr. high, the hardback first editions are among my prized possessions). Oh- and after the Kaiju and big special effects of “Pacific Rim” and “Battleship”, why can’t we get a cinema series based on Laumer’s “Bolo/Dinochrome Brigade” books, or Fred Saberhagen’s “Berserker” novels? Or are we doomed to endless reruns of the original “Star Wars” trilogy with different titles and actors? Seems only comfortable films are made anymore- comfortable in that the studio is comfortable that megabucks will be made. Sigh.

Yes, I always enjoyed Aspirin’s work. Another notable forerunner of the genre would be “Silverlock” by John Myers Myers (1949). L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt co-wrote some amazing, hilarious and delightful books in the “Incompleat Enchanter” series (1940 – 1941) – “The Roaring Trumpet”, “The Mathematics of Magic”, and “Castle of Iron”. Highly recommended.

I thnk those who have mentioned other series that precede Bob’s “Myth” stuff (and Thieves World) are missing the key to Asprin’s anthologies. Many authors have conjured up such consistent “worlds” (Laumer’s “Retief” books came immediately to mind), but…

Those I’ve read in the comments have all been penned by a single (or duo) author. Reiterating (nad reinforcing) what Anthony said, Bob Asprin’s genius, if you will, was managing to assemble a stable of writers – from himself to, say, CJ Cherryh, with people like Lynn Abbey and andrew j offut in between – all based on the world he created. Listening to him talk, it seemed like the most natural thing to organize an anthology. And yet, most authors didn’t want anyone else intruding on THEIR personal worlds, so it wasn’t “natural”. Bob made it so.

“Don’t believe I caught your name, Barbarian!”

“Don’t believe I droppped it. Nauseating, Y.T.”

(sorry I had to include that in any discussion involving Bob Asprin.)

#36: The cartoonist you’re thinking of is Jim Valentino. He did a one-off original plotline following Foglio’s run, and then an attempt at the second book that I don’t think was ever completed or collected. While Valentino had respectable humor chops of his own (his Normalman remains the definitive satire of 80s-era comics) Phil Foglio was a hard act to follow.

I agree that Foglio’s work is a rare case of an adaptation actually improving on the original in some ways. He expanded Garkin’s backstory in a way that explained both why a magician of his reputation would be slumming in a backwater dimension like Klah, and his willingness to take a half-starved thief as an apprentice; gave Isstvan a motivation that made a twisted kind of sense; and turned a minor plot-point from the novel into a excellent Chekhov’s gun In the final scenes. Not to mention the unique visual flair that is only his. And I loved the way he gave an extended cameo appearance to one of the Law Machines from his own Buck Godot, Zap Gun For Hire.

‘“That’s entertainment!” – Vlad the Impaler.

Best line ever. Of course, I don’t think you can have this genre conversation without including the “Joe’s world” books by Eric Flint. If the beginning of The Philosophical Strangler doesn’t get you hooked, you don’t do fantasy humor!

Thank you so much for this. The Myth books have always been my favorite fantasy comedy books (even though I also love a number of others already mentioned here), and I was heartbroken when we lost Mr. Asprin. This absolutely is a property that needs a visual adaptation, pronto.

@35: I second the Spellsinger reference, another fave series!

A favorite bit of dialogue I recall from the Foglio adaptation (wording may not be 100% accurate):

Aahz: Why, we’ll be famous, like Napoleon at Waterloo, the Light Brigade at Balaclava, Custer at the Little Big Horn.

Skeeve: Gee Aahz, you really think so?

Aahz: Kid, would I lie to you?

@39: there were remarks in his time about a hypothetical partner, Yin the Nauseated. Asprin did tend to inspire opinions. (And pranks — I’ve heard he was the one who gave an SCA stuffed shirt a stuffed lizard, then turned to the audience and said “All hail Sir Xxx: Knight of the Iguana!” That was the genesis of a filksong.)

@40: Thank you! At least I had the initial and something of the shape right. But now I’ll have to dig up the Foglio series, as I didn’t read Buck Godot until much later and don’t remember the Lawgiver Machine.

Thieves’ World was fine until one of the authors Mary Stu’ed her characters over the rest of the world.

Thanks for this item.

I figured “why not?” and started with book n⁰1.

Now I’m trying to get the rest in their original versions before they, just like Roald Dahl and Agatha Christie, get bowdlerised.

“A trollop was leaning out of a window …”

“I was afraid she would fall out … of the window or her dress ” :-)

I really had to cast my mind back a couple of decades to retrieve the meaning of the word trollop.

Big Julie likely was modeled from the character Big Jule in Guys and Dolls, played on the big screen by B.S. Pully. If he wants to give you his marker, why, you’d just better take it.

@48: Big Julie is also a parody of Julius Caesar, which is why his second-in-command was the Brute (Brutus). His forces appear to be a mashup of stereotypes of the ancient Italians (the Romans) and modern Italians (the Mafia).

I loved these when I was a kid. I think I got into them in junior high, and I loved them. I must’ve read the first four books about a dozen times. The series does take a noticeable dip in quality after #6, though, and I only read a couple of his collaborations with Jody Lyn Nye. But, this has me feeling nostalgic so maybe I’ll seek out some of the ones I skipped.

Are these books going to be put out in some kind of e-reader format? The paperbacks are getting old and I’m a bit afraid to check one out of the library in case it falls apart on me. I love these books!